Perfect Novels of the 20th Century

Four tasteful recommendations, if somewhat arbitrarily selected

Here is a list of four perfect novels, which I would recommend without reservation to any other literary soul. By literary soul I mean the sort of person for whom reading is much more like religious devotional practice than hobby. By perfect I mean the sort of novel which is unable to be improved.

What constitutes an improvement? I’d venture the following: a novel is improved when its text is altered such that it invites an excellent reader to more fully attend to the Image of God in man. A novel invites as opposed to compels or instructs, to name some other verbs I had considered using, because the meaning of a novel is not something that can be wholly expressed in language other than exactly that of the novel itself, and the text of a novel does not generate meaning deterministically, procedurally, or algorithmically.1 For reasons that I am not prepared to defend right now, I believe very strongly that we should evaluate novels by the meaning they convey to only the very best readers.2 Novels act upon their readers through the direction of their attention. I (think that I would, if I understand St. Augustine rightly) follow St. Augustine3 in framing God as being always and only the proper object of attention; attention to His creation is a way — in fact, the only way — of attending to Him, for he reveals himself to us only through His creative acts. The highest of these, of course, is the creation of man, and God uniquely reveals Himself through the Incarnation. Novels are forms of literature that are characteristically about human souls (sometimes in embodied anthropomorphic non-humans). Consider this to be partially a stipulative criterion of a novel — by novel I just mean only that literature about human souls — and partially a descriptive criterion to which I think that all putative novels probably adhere as a matter of fact.

I realize that I’ve hardly defended the thesis I’ve asserted, but the meagre clarifications will have to suffice. I want to tell you about books that I think are interesting. I have what I consider to be compelling and sophisticated reasons for thinking that they are interesting. These reasons are inextricably connected to my conception of what a novel is for. Thus, I have to tell you what I think a novel is for. But if I defended my view about what a novel is for at any reasonable length, I would never get around to telling you about the novels that I think exemplify the perfection of the genre, which is the thing that I’d really rather do, and I expect is the thing that you’d really rather read.

Anyway, there are many novels which can be improved. It should go without saying that for some novels to have never been written would constitute an improvement. That is, some novels actively make it more difficult for even excellent readers to attend to the Image of God in man, either because they are bad at inviting their readers’ attentions or the focus their readers’ attentions on things better left unattended to.4 But some novels will make you love your friends and your family and the fentanyl-addled stranger asking for your money and the brusque old church lady who hates your children and people far, far worse than even that — some novels will make you see Christ in your fellow man with such clarity and liveliness that to think of changing a word will break your heart. Some novels will fill you with the joy of the glory of love, and will shape your attention such that you will see for a moment how Christ could be the least of these and die for the worst of these.

So here is my non-exhaustive list of 20th-century candidates for perfection.

The Master of Hestviken/Olav Audunsson

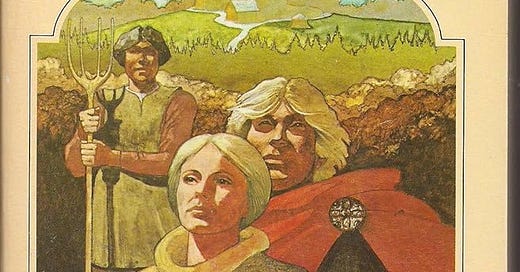

Sigrid Undset won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1928, but it would not be too surprising if you hadn’t heard of her. She wrote in Norwegian, but her strongly Lutheran countrymen rejected her for her vocal conversion to Catholicism, and the Anglophone literary world lacked an accessible translation of her work until recently. Some people will tell you that there was no good English translation of her work; I have read her two multivolume medieval novels in both English translations and, while I would agree that Tiina Nunally’s recent translations are likely better (insofar as I am capable of judging at all, given that I don’t even know how to pronounce Norwegian diacritics), I do find the deliberately archaic voice of the older translation to be charming. If you have heard of Undset, it’s likely because of her excellent novel Kristin Lavransdatter, which I would have thought perfect until I read Hestviken; Hestviken is the perfection of Kristin Lavransdatter. Apparently the Norwegian title of Hestviken is something that might be rendered Olav Audunsson, the Master of Hestviken, but the two English translations have confusingly been titled The Master of Hestviken (old) and Olav Audunsson (new).

Like Kristin, Hestviken tells the childhood-to-death story of a titular 13th-14th century Norwegian noble, vividly rendered acrossed more than 1000 pages of conflict between Christianity and paganism, husbands and wives, houses and retainers, priests and laity, parents and children, the quick and the dead. The back jacket of my ancient single-volume copy of Hestviken5 describes Undset’s characters as “timeless in their humanity.” It’s more than that. It’s that they are all you; their children are your children, and you are their children, and their parents are your parents, but you are their parents too. You are folded into the entire human race, and you see the entire human race folded into you. You’re not you, you’re everyone else. Undset more than anyone else has revealed to me the murder in my own heart alongside the Image of God that I bear; I see myself in both horror and in joy reflected in every one of her characters.

When Christ hung from the cross, he prayed regarding his torturers: Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do. The message of the Gospel is twofold. First, you are relevantly like the Roman soldiers; there is some part of you under the dominion of the demons, some part of you which is like the person who would torture to death a demonstrably innocent man. Second, you can — and will — be totally unlike that; He will make you into the kind of person who could look upon his torturers and forgive them utterly. Undset’s stories are this Gospel repackaged. Hestviken, more than her other work, grapples with unfathomable darkness: infidelity, child abuse, infanticide, lust, murder, and all manner of cruelties both extraordinary and commonplace. And yet also, more than her other work, the life of the hero which should by all rights end bitterly, tragically, horifically even, is suffused and overcome by penitence and forgiveness which transforms his children; he is in turn transformed by their own penitence and forgiveness. Hestviken is the story of a man becoming like Christ, and through him, the redemption of all things commences. The vision of Undset’s world is eschatological: we wait, in an admixture of suffering and joy, for God to save us. But the waiting is not passive. It is a long and gradually triumphant struggle toward a God who we will never reach of our own power, but who will Himself reach down to retrieve his creation to heaven, piece by piece.

The Silmarillion

Nobody understands Tolkien except me.

That’s false. But I resent his popularity sometimes. Yes, he really is that good; he deserves to popular, deserves to be celebrated as quite possibly the greatest English-language writer of the 20th century. The reason I resent his popularity is that it doesn’t seem like most people who want to celebrate Tolkien want to do so for the right reasons. Tolkien’s achievement is principally one of language, and The Lord of the Rings is in some respects the great modernist novel, whose prose ranks with Joyce.6 The novel’s thematic and narratival sophistication exceeds the encyclopedic postmodern novels which would emulate (if indeliberately) Tolkien’s thoroughgoing realism; that is, his commitment to seeing his world so vividly rendered that it is hardly believable that is is a creation rather than a discovery. Its metatextual conceit (the Red Book of Westmarch), and its ear for dialogue (attend to the accents; if Tolkien had pulled a McCarthy and abstained from using dialogue tags you would still almost always know who is talking), and its capacity to shift registers suddenly but not jarringly by simply becoming selective about the etymology of words (high register sections — the Pelennor, for instance — eschew Latinate words and rely on primarily if not exclusively words with Germanic roots), and its willingness to convey narrative in large sections of chained preterites, and its burial of almost all subplot in subtext, and its pages of untranslated Elvish — these features are so entirely innovative and compelling that it pains me to encounter people whose principle interest is in which character could beat which in a fight, or who want to know what the Ring does, or who wonder whether Galadriel can be regarded as a feminist, or who wring vague political platitudes out of this beautiful story in ugly “traditionalist” Catholic thinkpieces. These kinds of readers annoy me because The Lord of the Rings is not so much fantasy novel7 as it is a vehicle for transmitting the medieval imagination to the modern mind.

People don’t have to get any of this to get The Lord of the Rings. If someone thinks that the relevant comparison to Tolkien is Dungeons and Dragons or (Christ have mercy upon us) A Game of Thrones, I don’t necessarily even doubt that their appreciation is well-founded. You can be a good reader without being very good at talking about what you’ve read, or being able to make explicit your good reasons for liking something, and you might mistake them for reasons that are quite bad.

But one reason why I love The Silmarillion is that it disinvites the bad sort of reader from the outset. The kind of person who would ask, “Could Feanor beat Fingolfin in a fight?” is unlikely to make it past the Ainulindale. Part of the genius of The Lord of the Rings, which has contributed significantly I am sure to its commercial success, is that it guides the reader back in time with the help of Hobbits, effectively contemporary Englishmen, who ride along with you and help you digest the progressively mounting strangeness of the old world. Part of the genius of The Silmarillion, which has contributed significantly to its relative lack of commercial success, is that it baptizes the reader in Tolkien’s medieval worldview from the outset. To some it may seem that The Silmarillion is all fat — “lore” for Tolkien’s main story. But the opposite is true: The Silmarillion is the lean and powerful sinews of a myth that ranges from the ineffable and cosmogonic to the level of medieval romance, in the service of synthesizing Christianity with an element of Germanic paganism that Tolkien called “the Northern Theory of Courage.”

The Norse believed that the world was going to end one day. If you were virtuous in this life, you got to spend the afterlife training to fight the monsters who would devour the world at the end of time. No matter how well you trained, however, the monsters would win. The Northern Theory of Courage is the view that even when the odds are totally impossible there’s something beautiful and worthwhile about an obstinate refusal to admit defeat.8 But the Christian view is that ultimately the monsters are defeated, cast into the lake of fire prepared for the devil (“that old serpent” as God’s favorite translation, the KJV, has it) and all his works. Can we make the intuitive appeal of courage in the face of hopelessness coherent with the impossibility of hopelessness on the Christian account?

Tolkien’s answer is the eucatastrophe, the good catastrophe. At the moment when all seems lost once and for all, some savior unlooked for appears in the darkness and dispels the forces of Hell. But for Tolkien the eucatastrophe doesn’t work if it’s a simple deus ex machina. For it to be compelling, it has to come through the workings of providence — it has to not merely undo mortal folly or reward mortal effort, but redeem folly and operate through effort. So for instance when at the Pelennor Eomer sees the black sails of Umbar arriving on the river and knows that all is lost, for Mordor’s reinforcements have arrived, he charges to meet a glorious death in battle against them, and then who should disembark but the returning king of Gondor commanding the army of the dead. And Aragorn, meanwhile, has no hope of reaching the Pelennor in time, but sails anyway, and an unlooked-for west wind rises and speeds them upriver to reinforce Gondor and the Rohirrim before all is lost. Faithfulness in the face of certain doom brings about a eucatastrophe where the field of the Pelennor is won against all odds. Rohan rides to Gondor’s aid, expecting slaughter; Aragorn sails to Gondor’s aid, expecting to be too late; Rohan forestalls the fall of the city until, aided by the wind (a divine gift), Aragorn can arrive to at last turn the battle.

On the level of metanarrative, however, each victory but forestalls a final defeat — and a final eucatastrophe. There is a kind of temporal hopelessness that pervades Tolkien; as Galadriel says, she has “fought the long defeat.” Every victory is but a setback for Hell, whose forces will progressively gain ground until God has no recourse to but to act once and for all. It is here that The Silmarillion succeeds where The Lord of the Rings leaves off; in the same way that Hestviken perfects Kristen, The Silmarillion perfects the rest of Tolkien’s ouvre.

The Silmarillion is the cosmic story of eucatastrophe and long defeat: it recounts thousands of years of history, of war between gods and the fall of the Elves from paradise into a cruel world where they make war against Morgoth (an obvious devil figure) and yet at the same time emulate him in betrayals and lust and rage. It is like Milton but older and not wrong; Tolkien’s Morgoth is really the devil and the fall is the beginning of the great war against him. The best comparison for The Silmarillion is the Old Testament — the story of the people of God (Feanor, Maeglin) repeatedly betraying themselves into the hands of demons (Morgoth, Glaurung) while their greatest heroes (Beren, Earendil) sacrifice themselves for their faithless people, and in the midst of all their faithlessness, at the moment when all is lost, the heavens open and the Angel of the Lord (the Valar) breaks down the doors of hell (Angband), but only through, and because of, the faithful sacrifices of all the saints and martyrs (Elf-friends and their children) through all of time.

I don’t know if the The Silmarillion is objectively better than The Lord of the Rings. But to me it seems the real thing, the thing to which anything else by Tolkien is only an introduction. The Lord of the Rings moves me to tears of anguish and of joy, and to laughter. The Silmarillion moves me to grief and joy beyond tears. I am only silent and stone-faced when I read it. Whatever The Silmarillion conjurs inside me is too holy and incensed for expression.

Lonesome Dove

I wouldn’t have counted myself a reader of Westerns until recently, but I guess I am now. Larry McMurtry’s magnum opus follows retired Texas Rangers Woodrow F. Call and Augustus “Gus” McCrae as they take a crew of young boys and a recently reformed prostitute on a cattle drive from Lonesome Dove, Texas to start the first ranch in Montana. The prose is sparse and simple. There’s even a lot of telling, not showing, which is refreshing in a world full of literary gruel served up by first-person-present-show-don’t-tell-MFA-grads. It’s not Hemingway sparse — there are plenty of adjectives. Rather, it’s sparse like how my family from Texas talks: they’ll tell it like it is, and they don’t much think about which words they use, other than that they use the words that’ll get the job done. Which is perfect for a Western.

And the dialogue. It’s so, so good. One character loses his saddle in a bet. Gus tells him, “A man who’s dumb enough to bet his saddle is dumb enough to eat gourds.” And without further commentary from McMurtry, the poor cowboy replies, “I have et okra, but I have never yet et no gourd.”

Referring to the great extent of animal remains littering the prairie, Gus says, “The whole world is pretty much just a boneyard.” Then, after a pause: “But it’s pretty in the sunlight.”

The whole novel conveys this sort of understated cynicism in the language of cowboys, whose heroic actions belie the hardness of their words. They die for each other and for strangers and sometimes for nothing, and they laugh about their own deaths with courage while they mourn the fallen with reverence, and they live in world where storm and plague and evil, evil men threaten them and those they love and innocents who they don’t know but would hate to see suffer, and their response is to saddle up with their guns and do their damndest.

They’re also all cowards. They love too much their comforts and their thrills. They abandon their wives and children — not often to danger, but to loneliness and drudgery while the cowboys conquer the west. They’re fools who drink too much and buy sex at every opportunity. Sometimes they suffer for their folly. More often others do. A good chunk of the men die, and there’s a terrible amount of violence directed against women and children. The world of Lonesome Dove is cold and terrible sometimes. Maybe even usually, in the end. It’s hard to tell, because it’s pretty in the sunlight.

McMurtry doesn’t seem to have an agenda. He doesn’t care if I believe it all can be redeemed by the love of Christ, or if I think that we’re already living in hell. But his vision is one of love. He loves the people of the American West — cowboys, prostitutes, ladies, fathers, mothers, daughters, sons, brothers, wives, sisters, husbands, friends. He loves them even though they’re wicked and cruel to one another sometimes, even most of the time. He hates only the devil. And the devil is real. He haunts these pages in many guises, chiefly but not only as Blue Duck. He gets what’s coming to him, sort of, though not in a final way.

Lonesome Dove asks you if you can love a person if you really, really know him or her. If you know what that person is like, and everything that he or she did, and might have done in different circumstances. It asks you if you can love people — the whole human race — if you know what people are like. And it answers: yes, you can. They will grieve you sorely and in the end they won’t deserve your love or whatever happiness they find, if they can find any. But reading this novel will make you the kind of person to forgive them, and wish them happiness, even when they’ve done nothing right.

In other words, Lonesome Dove presents you with a cast of men and women who mostly turn out to be villains, even if just in small ways, and who all end up suffering for it, often in big ways. But McMurtry loves them all so much despite this that you can’t help but loving them either. This is a novel that might give you a sense of God’s disposition toward a rebellious creation. Nobody does what you wanted or expected. McMurtry himself said he always hoped and expected that Call would find the courage to claim Newt as his son; but Call never does, and the most he can do is give the boy his horse. But you still hope, in the end, perhaps beyond the grave, that Call will find some little happiness, and that Newt can find it in himself to forgive his father, and and you hope for Gus, and Lorena, and even Jake Spoon, and most everyone else too: to happiness that they don’t deserve, but you wish them nonetheless, because you can’t help but love them amid all their self-wrought suffering.

Infinite Jest

It’s hard to write about Infinite Jest without a preamble acknowledging the hordes who have written about it before. But I think what others have to say about it is usually boring, so consider this the extent of the preamble.

The metatextual conceit of Infinite Jest is that it is written by one of the main characters, Hal Incandenza.9 Specifically, the novel Infinite Jest is the anti-entertainment, an antidote to the titular film Infinite Jest, which is the lethally entertaining maguffin of the whole story. Hal’s father, James O. Incandenza, was a tennis prodigy, wildly successful nuclear and optical engineer, and avant garde filmmaker. He makes short films like Various Small Flames, in which shots of candles, pilot lights, and other household flames are interspersed with shots of a man sitting on a bed while his wife and another man have “acrobatic coitus” in the background. This is explained in a 10 page plot-essential endnote that lists Incandenza’s entire filmography. It boggles my mind when I tell this to people and they don’t immediately go pick up the novel. Doesn’t this sounds hilarious? Because it is. It’s hilarious to make your reader read endnotes. It’s hilarious to list a fictional filmography in an endnote. It’s hilarious to concoct such an absurd arthouse short film for a fictional filmography. And the phrase “acrobatic coitus” is vulgar, yes, but hilarious. I laughed out loud throughout this novel. By the way, most of the novel is set in the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment, in which the Statue of Liberty is swaddled in an enormous diaper, but parts of it are also set in earlier years, such as the Year of the Whisper-Quiet Maytag Dishmaster.

Anyway, one of Incandenza’s film is the titular Infinite Jest, which goes through several unreleased, failed iterations. When he completes the final iteration, he “erases his map” i.e. kills himself, by microwaving his head (also kind of funny, no?), and someone starts disemminating copies of the film. The film is so entertaining that anyone who sees it loses all interest in anything else and enters a comatose state, eyes glued to the television — sorry, teleputer — until they simply die, and a cell of wheelchair-bound Quebecois terrorists is trying to find the master copy of Infinite Jest so they can broadcast it across O.N.A.N (Organization of North American Nations) and force the United States to take back what they label the Great Convexity, but which we U.S. folk call the Great Concavity — an irradiated land of feral infants and other mutants that comprises a large swath of what used to be New England which was “gifted” to Canada when they merged with the U.S. to make O.N.A.N.

But the real kicker is that Hal Incandenza has this weird condition where his father cannot understand his speech, even though he (Hal) is the most articulate person to ever live, and this condition begins to gradually affect his attempts at conversations with others, until he is incapable of speaking in any way that sounds like something other than demonic babbling. James, experiencing this condition early on, became an avant garde filmmaker in an attempt to communicate with his son. Every attempt failed, so he killed himself.

But Infinite Jest (the film) didn’t fail. It succeeds too much. This is all buried in the novel’s subtext and never stated explicitly (much like my claim that Hal is the author of the novel Infinite Jest). But what happens is that the Wheelchair Assassins are sort of successful and the entertainment is weaponized. Hal saves the day by writing Infinite Jest, something so engrossing and yet not merely entertaining, but instead meaningful and awful and really frightening, that it can break the spell. And in doing so, of course, he communicates with his father. Hal writes something in response to his father.

That’s what I would maintain the novel is about — although good luck looking for explicit confirmation of most of my synopsis within the text. What is actually in the novel, the stuff that comprises the antidote to the entertainment, is what one real-life reviewer called a “1000-page encyclopedia of hurt.” The novel is a series of vignettes that are hysterically funny in a dark, Burn After Reading sort of way. These stopped being funny about halfway through, to my mind, when they started becoming sincere. There was no change in the text, it’s just that, after 500 pages of suffering and ironic jokes about suffering, the jokes provoke more tears than laughter.

There’s this really incredible scene in the Fourth Book of Moses, commonly called Numbers (as God’s favorite translation titles it), where the Israelites are all dying from venemous snake bites, and God recommends that they try this insane new cure he’s been cooking up (doctors hate him!): “And Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived.”

Infinite Jest (the novel) is a type of bronze serpent. The venomous snakes are our entertainments, embodied in their extremes in Infinite Jest (the film). The antivenom is in the beholding. We suffer for our vice; our suffering drives us to more vice: substance abuse, sexual dysfunction, cruelty, insanity, suicide. These leave only more suffering in their wake. The cure is to stare at these sins. If you really see what alcoholism does to a person, the temptation to alcoholism dies.

The Gospel accounts explicitly paint Christ as the fulfillment of the brass serpent. He is lifted up on a pole; and when we behold Him hanging from the cross, we behold the sins of the world — all the venemous serpents, all the things that are killing us, brought together in one place and bearing down on one man. To see Christ dying is to see all of the evil in the world, for here is a man who has only ever loved, who now dies for no cause save our envy, and we torture Him because we resent His love for us. But if we really see Christ hanging there, we will see what we’ve done, and we will repent: we will be cured. This one reason why every church10 has an icon or crucifix or stained glass representing the crucifixion or at the very least a cross, usually front and center — we’re supposed to look at the brass serpent.

Thus Infinite Jest (the novel) is a Christ-figure. We stare into it and see all our wickedness and vice for what it is: horrifying, ugly, grotesque. We see our normal coping mechanisms — humor and irony and entertainment and liquor and sex and anything else you can think of — gradually dismantled; they are insufficient to the task. Comedy becomes grief as satire becomes sincere; just as the pleasure of vengeance on God vanishes when we realize what it really means for us to drive a nail into His hand. We realize, then, that the only answer to our suffering is radical repentance. We have to stop joking about evil and do something about it. Perhaps this is why so many have found Infinite Jest a great help in overcoming their own addictions.

But also buried at the root of the novel is a deep pessimism about the ability of humans to do anything about their own evil. Thus Wallace-Hal demands of his readers an ultimate surrender to the divine, just like AA demands its members — and many of Wallace’s characters are AA members — surrender their will to a “higher power” in order to escape their addictions. You cannot remain your own; you can do nothing of your own accord except to give yourself into the hands of something better which can do something. The Wallace-Hal answer to the evil-entertainment problem is repentance in submission to God, or at least to something very like God. This comes through in so many spades that it’s a wonder to me the novel is not thought of as one of the great Christian novels in the way we think of, say, The Brothers Karamazov.

In other words, we’re all watching Infinite Jest — the lethal entertainment. The only way to escape death is to read Infinite Jest instead. And this reading is itself an act of submission to something other than yourself; it’s a surrender of your vision to something beyond you — in fact, to a word, if you will. The majesty of Infinite Jest is its participatory nature: rather than read the story of Christ, you reenact it. You, the reader, play the sinner, and the book plays the incarnate Word.

Concluding thoughts

As I reflect on the list I’ve given, general thoughts strike me. First, all the novels are exceptionally long. I’m not sure if this reveals something about perfect novels or if it merely reveals my own idiosyncrasies or pathologies. Second, though I only have drawn an explicit connection between the Old Testament and The Silmarillion, all of these novels really do have a certain ineffable quality reminiscent of the Pentateuch. Third, of these four works, The Silmarillion is without a doubt my favorite, though The Master of Hestviken is probably the best. Fourth, only Hestviken is a traditional novel. The others are all weird and experimental in their form, in one way or another.

Fifth, each of these novels seems to be deeply preoccupied with theodicy. The view of each seems to be that human beings can hope for no redemption unless God elects to save us. This view naturally raises a question: if there is a God who will save us, why hasn’t He yet? Or, more baldly, given that He hasn’t, is it reasonable to hope for redemption at all? Tolkien, Undset, and Wallace all answer affirmatively — God comes out looking okay. And they aren’t wearing kid gloves: they call God to account for the most excruciating suffering you can think of, and even some you can’t. McMurtry is a bit more agnostic, I think. The position that Lonesome Dove seems to strike is something to the effect of We’re not sure if God will save us. But there’s something beautiful in us that God would want to save, if He were out there.

Sixth, there are a lot of conspicuous absences from my list. That’s because I’m not very well-read. I read widely, and, I think, excellently. But I don’t in the main read novels, and I’m no expert on the literature of any time period. If I have any expertise at all it’s in price theory, early 20th-century economic thought, and 11th century canon law, so, take anything I have to say about literature with a grain of salt. I have read no Faulkner nor Updike nor Steinbeck, and very little Hemingway. I read pretty indiscriminately — if someone I trust says a book is good, and I find it at a reasonable price at a used book store, I buy it and read it. The order of my to-read list is thus largely in the hand of providence, which might be healthy. But I’m trustworthy as a reader at least in this respect: I’ve largely escaped the vice of reading books just because I want to be the kind of person who has read them. Reading is too sacred a pleasure for me to squander in the pursuit of impressive bookshelves.

Recently my grandmother gave me her old annotated copy of The Sound and the Fury, and I managed to score a single volume edition of Updike’s Rabbit novels for $3.95 as well as a copy of Middlemarch from a recent trip to McKay Used Books in Manassas, VA (cannot recommend strongly enough a pilgrimage to this store if you’re ever in NoVA). So my summer reading will rectify some deficiencies, I think.

I’m not sure if I mean something different by each of these three adverbs, or if they are synonyms. Perhaps think of them as mostly overlapping terms that perhaps connote some different referents, all of which I want to exclude from the category of ways in which a novel produces its meaning.

If you want to think more about this suggestion, I strongly recommend Lewis’ An Experiment in Criticism.

Specifically in the first few chapters of On Christian Doctrine.

A related hypothesis to which I cling with some convicition but which I would be hard-pressed to cogently defend is that any novel attaining to formal excellence is excellent. That is, if it successfully invites the excellent readers’ attention at all, it will of necessity invite attention to the Image of God in man. For this hypothesis to be even remotely plausible, the word excellent in excellent reader has to do a lot of work. But I think excellent might be up to the task. This is because I a) consider myself to be an excellent reader and b) have only once ever met a novel considered good by literary standards that I did not love (this novel was Jude the Obscure, and I confess I read about 40 pages and thought it to be a complete mediocrity and that I’ve read much better mass-market genre fiction), and c) since my baptism, have never met a novel that I loved which did not produce an improvement in either my prayer life or my relationships. These stylized facts are surely not enough to elevate my hypothesis to anything more than a hypothesis — but it’s at least suggestive, right? Interestingly, I also feel similarly, though less strongly, about film and music, but not other artistic media. For instance, I think Gauguin’s work is completely hideous. That may merely evidence lack of training; I am unsure.

A Christmas present, years ago, from my mom — I don’t know where she found it.

Tom Shippey convincingly defends this thesis in The Road to Middle-Earth and Author of the Century.

And it is ASSUREDLY NOT a fantasy series; it is SIX BOOKS comprising ONE NOVEL which is only split into multiple titled volumes because of the historical accident of a post-war paper shortage, and the titles of the volumes are placeholders that sometimes make very little sense. For instance, there are no fewer than six named towers in “The Two Towers”, and Tolkien himself seriously regretted that title in particular. The referent towers were intended to be Orthanc, of course, and, far less obviously, the Tower of Cirith Ungol. One of Peter Jackson’s few inspired improvements in the production of the films was to explicitly name the towers as Orthanc and Barad-Dur, the latter of which is not very much the subject of Book IV, but is in general much more focal.

I think it is likely that Tolkien has shaped my imagination more than anyone else. (I read The Silmarillion four times in a row when I was twelve — it has been basically my favorite book ever since.) But this feature of Tolkien, the Northern Theory of Courage, I think bears some resemblance to Camus’ worldview, which might explain a period in my later youth where I was quite invested in Camus’ work. See in particular the doctor from The Plague for a really good example of what sounds to me rather like the Northern Theory of Courage.

Has anyone said this before? Someone must have, because it’s so obvious. But anyone I’ve talked to seems to have missed this fact. I don’t know how on earth you can make sense of the novel without it.

Except our dear iconoclast brothers and sisters in the Reformed tradition.

Love the shout-out to Olav Audunnson!

Great essay. Random thoughts: I do think GRR Martin, while not as linguistically savvy, is if not Tolkien’s heir, at least his bastard son. People always contrast them but I think there are more thematic commonalities than differences.

Second, brain-rotted zoomer I am I still think show not tell remains underrated writing advice. I just finished Moby Dick and honestly Melville could have done a little more showing! Everyone says it but nobody does it. And yet somehow so few writers can write a character that says one thing and does another. There’s a lesson in that.

Lastly, did you ever read Cane? I’m sure I told you about it at some point.